Key to understanding what life was like in the US Army is the realization that, for the average GI, going off to war is a relief

and a welcome diversion from the monotony and regimented busywork of garrison life. Perhaps someday I’ll write up a lengthy listing of what life was like for me in Germany pre-Jan 2003, before we shipped out to Kuwait. If you want to see a video of us doing Engineer training in Grafenwoehr, click here. For now I’ll focus on the “Highlights” from the war.

I broke up with my 18-month German girlfriend in September ’02. The US was in Afghanistan & the rumors were flying about Iraq. Everyone wanted to go, but we were scheduled to go to Bosnia instead. October we were given the official green light: We would be one of the first units to go to Kuwait, in preparation for an invasion of Iraq. Tough luck Bosnia. We packed all of our vehicles like mad dogs in the snow in less than two weeks and “railed” them(loaded them on the German trains) all up to Antwerp for cargo ship to Kuwait.

We(Charlie Company) were the only company in the 54th Battalion activated, based on our stellar record in training at Grafenwoehr, so we were given carte blanche by our colonel to “appropriate” anything needed from any other vehicles. We “appropriated” damn near everything, nailed down or not. I vividly recall Bravo Co’s A&O(Assault & Obstacle) Platoon Sergeant snarling at me for removing the U-bolts holding his 15,000lb MICLIC rocket box to the trailer. “Sorry Sergeant,” I said, “just see the Colonel”. Ah, the good old days.

The rest of the battalion was activated a week later, then we helped them load their(stripped) vehicles for a further two weeks.

Then we lounged around for another month of false alarms before finally getting the go-ahead to fly. We kept busy, getting all our checkups, wills, shots, loading our cars in storage, trading schlampes, trying to drink Bamberg dry, etc. I remember feeling extremely satisfied to hear 82nd Engineers(the “competing” Engineer Bttn on our base) grumbling about having to guard the base during the German winter without us.

We arrived late at night and took a bus into the middle of the desert to Camp Virginia, our new home for the next month or so. Here we prepped for the possibility of war. There was still no confirmation whether there would be one. Even though it was January, I was only comfortable outside at night, when the heat subsided to mere oven-like intensity. During the day we sweated our balls off.

We spent the first few weeks getting used to “Desert Life”. Disheartening experiences were routine, like waiting two hours for food in the heat of the day, only to find that the AC in the chow hall was only half functioning. Have you ever tried to eat at temperatures over 130?

Not that the food was much to get excited about anyway.

We never exercised but all started losing a lot of weight anyway.

After two weeks of enjoying the company of 100 other sweaty, pissed-off men in one big tent, I was overjoyed to finally greet my dear “Battle Buddy” George Peterson, Perpetual Specialist(tho I hear he finally “got his 5″ recently). I gave him the grand tour; “This is the two-hour chow hall line, this is the the two-hour PX line, these tubs are where we do our own laundry, your company’s shower time is 0400-0600, these portapoties will be your new friend. You didn’t bring any TP, you say? Tsk tsk”. I wore a mark into my left side BDU thigh pocket from the roll of portable TP I carried everywhere. Here’s a picture our German buddy Kim put together to show George on vacation in Kuwait:

Shortly after George arrived, a company-sized(100 men) contingent was assembled from the four companies in the battalion and sent down south to “the Port” to unload vehicles. Most of the crew was from C Co, as we had been “in country” most and therefore could spare the time, it was figured. The soldiers who were picked from each company were those deemed least useful so of course George and I went. We were initially dismayed at the prospect of actual work, but it turned out to be an absolutely fantastic experience, one I look back on with vast pride and accomplishment. Once the boat was ready the system worked like this: We would catch a ride in or on top of anything going to the port. The boat(It was a huge commercial freighter) crew would unchain the vehicles, then drive them down to the staging area, typically with the parking brakes on, leaking fluid & leaving a trail of tools & personal items. Upon our arrival, we would leap out of the still-moving transport vehicle and race each other to the most interesting-looking vehicle and then further race each other along a remote Kuwaiti highway until we got to the Motor Pool Yard. Extra points were awarded to those claiming the weirdest vehicles, especially wheeled ones. We drove giant cranes (often tipping them over), firetrucks, fuel trucks, bulldozers, and lots of other vehicles we could not guess at the function of. Tracked vehicles had to wait to be loaded up on HETTs, big flatbeds, then they were dropped off at the yard, so we tried to get the wheeled vehicles, naturally. Once in the Yard, our route went a few miles back behind the massed vehicles across a hugely rutted sand track that we naturally hurtled our poor charges across at top speed. I recall catching “serious air” in an M113 over one slight rise. If the vehicle belonged to an evil-headed SOB in another company we might take certain liberties with the paint, or stored tools, or we might just play “Bumper Tanks”. Come to think of it, they were all SOBs.

There was a lot of “mixed company” at the Port. Marines, Air Force(God I loved their latrine trailers!), British and other Coalition soldiers. I talked to one older British fellow, to direct him to where he could get a cup of tea. Since he had a big crown on his rank-strap I gave him a salute, and he returned it, in the humorously open-palmed British fashion. When I started calling him “Sir” though, he had to correct me. “Th’ big crown’s fo’ a Sergeant Major, th’ little crown means a Major. Shows th’ relative importance.” I told him that, while we were on the subject, he probably shouldn’t call me “Sir” either and he said “I thought you were a touch young for a Colonel” pointing out the eagle on my Specialist “Teardrop”. “So why did we salute each other?” I asked with a smile. “That’s OK lad, I was just keepin’ the sun out of me eyes.” he replied.

Re-acquaintance with the rest of the battalion up North was very anti-climactic. We downloaded our vehicles,

worked on our vehicles(conveniently painted German Green for the desert environment), held classes on techniques for desert warfare, turned more wrenches, practiced tactical driving and fixed our vehicles some more. To get a good idea of what life in the kind of situation is like, read this essay on How to Deploy.

1st Platoon rocked.

Had a good laugh when saw a flat-bedded M88(Tank recovery vehicle) with the boom left up grab this Iraqi road sign.

The driver & TC scratched their heads for a while, then drove off, taking the sign with them. I wonder if it ever turned up on ebay.

Mar 25

The next day, the wind started to pick up and one side of the sky turned orange. I had seen sandstorms before, but never that turned everything orange. We were headed North again, and I got called over the radio to tow “Rock 8″, which was the company TOC–The Tactical Operations Center in an M577, which is basically a taller M113 that you can stand up inside. I hooked up and started to tow but then had to slow down because I couldn’t see a damn thing in front of me. It was only 1300 but the sandstorm made everything look reddish-orange as Mars and dark as twilight. Looking behind me, I could make out the 577 with Sergeant Showers pulling security on the top of it with a shirt wrapped around his face and goggles on but I couldn’t see more than a few feet in front of me. I had worn my prescription-strength sunglasses every day for the last three months and couldn’t find my regular glasses anywhere at that exact moment(they later turned up). I suddenly had a revelation and put on my gas mask, as it had prescription inserts inside. Despite the heat, it was actually much better from the sandstorm with the mask on. I turned around and gave Sgt Showers the thumbs up. A minute later, we hit a big bump and I turned around to see how they were doing. Showers and his driver, Acker, had thrown their weapons in their hatches and were frantically pulling on their chem suits with their masks on. Turns out they had lost comms along with their motor. It took a few minutes for me to visually interrupt and re-assure them that they weren’t going to die. They later thought it was funny. Much later.

Here is our M577/TOC parked next to some CAV TOCs.

We could always tell our vehicles apart, since they were painted damn green, while everyone else had theirs tan. Also, ours always had more shit stacked on the tops, went slower, and leaked 15-40.

We parked on a road. I don’t know more, since I never saw any more than just the road. The wind wasn’t bad–I later learned that Iraq has these weird high-altitude dust storms that block the light without much wind every 50 years. We were just really lucky, I guess. That night I had two hours of guard, and it was one of the most bizarre experiences of my life. There was no wind or noise at all, but no way to see anything. I literally pressed my hand to the end of my NVGs and couldn’t see anything. When I turned on a small red light inside of my track with the hatch open it looked like thick snow falling. To guard we had to walk down the line of vehicles, touching each one to keep from getting lost. Flailing around in empty air after the last vehicle was a terrifying experience. Three guys stepped too far away from their tracks and spend the night in the ditch.

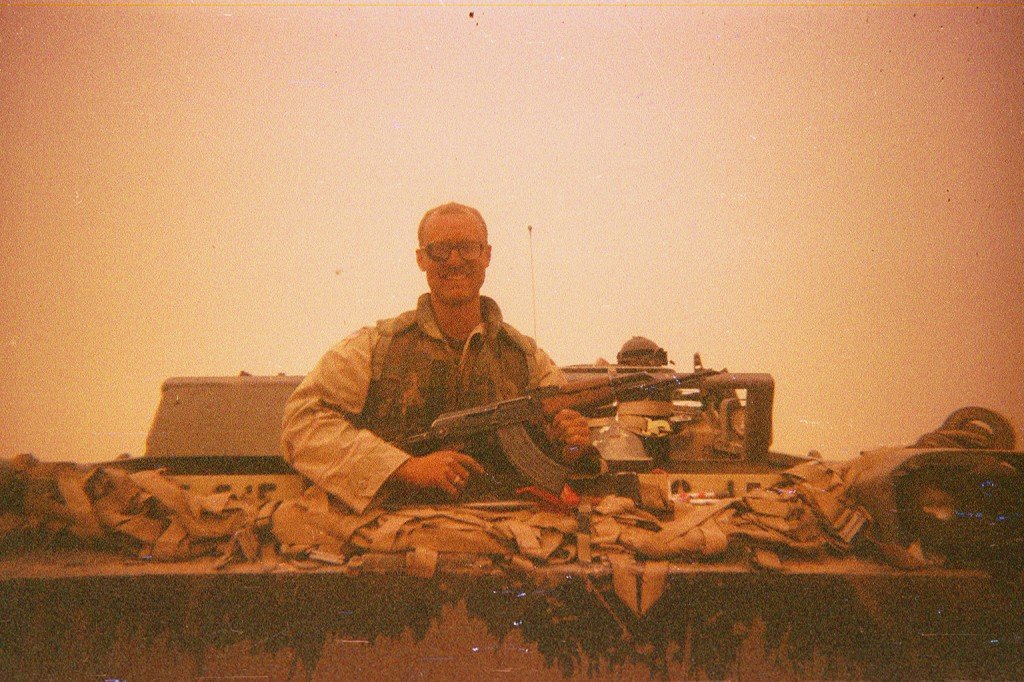

I picked up an AK right about this time.

It was funny to see what happened to ordinary people under the strain of combat. PFC Judalena freaked out and abandoned his ACE & equipment. Another soldier who we all thought was pretty hard-boiled abandoned his Humvee and jumped into the back of a 5-ton, where he cowered while the lead flew. My normally-competent squad leader, Sgt Hutch, turned into a blind idiot. My LT fell asleep. I always had to take a dump. Such is life in a war zone.